I Love Library Booksales

I have the good fortune to work in a major public library, and our booksales always have a linguistic treasure or two. This season’s booksale just finished, and I picked up two books on Swahili (one a dictionary, one a “Teach Yourself” title) and a dictionary of German synonyms.

At other booksales, I’ve picked up books on learning languages and, a number of years ago, one outlining all the similarities between Scandinavian languages and Native American ones (trying to “prove” that Eastern Native American languages were directly related to the Viking settlers of North America, if I remember correctly).

There have been some ones I’ve kicked myself for not buying. I’m thinking especially of last year when I saw a complete set of The Lord of the Rings in a Russian translation. Saw it lying on a table and thought, “Oh, I need to stop back around and pick that up.” By the time I came back, they were gone. I even remember looking through them a the time and thinking, “Ah, no translation of the Appendices.”

Oh, well, I can curl up with my German synonyms, and see how I can create some vocabulary. Sure, I could have used a Roget’s, but synonyms in another language than English seemed a more interesting way to go.

Anyone willing to share any finds they’ve come across at library booksales?

A Little Lexical Inspiration

I recently picked up the book Pacific Languages: An Introduction by John Lynch from the library and was leafing through it. Lots and lots of food for thought from languages from Adzera to Yukulta. This evening, as I was looking over Chapter 11 (Language, Society and Culture in the Pacific), and found some good lexical inspiration. I’ve read a number of times on various conlanging listservs and boards about looking for different ways to split up concepts that may be lumped together in one’s own language. Well, from this book, it appears Yidiny does a good job of illustrating this:

dalmba – sound of cutting

mida – the noise of a person clicking his tongue against the roof of his mouth, or the noise of an eel hitting the water

maral – the noise of hands being clapped together

nyurrugu – the noise of talking heard a long way off when the words cannot quite be made out

yuyurunggul – the noise of a snake sliding through the grass

gangga – the noise of some person approaching, for example, the sound of his feet on leaves or through the grass — or even the sound of a walking stick being dragged across the ground

I for one would not have thought of assigning lexemes to those concepts.

Additionally, Pacific Languages: An Introduction provides a reminder that even different stages of a coconut’s growth can be assigned different words: a coconut fruit bud (iapwas), young coconut before meat has begun to form (tafa), nut with hard well-developed meat (kahimaregi), etc., etc., etc.

Hmmm, all these languages have me thinking about my own Elasin after a looong hiatus. Might be time to go back and start “reconstructing” the work of Paiwon Lawonsa on the Uhanid languages.

Conlanging and Conworlding Are &%$#@ Hard!

The first reaction of most everyone who reads this will most likely be "Duh!" To this, I’d add "I know, but sometimes it just hits you like the proverbial ton of bricks." And by hard I don't simply mean difficult. What I'm specifically referring to is the urge to be original or unique in one's conlanging/conworlding efforts.

Over last weekend, I was out at our local Borders buying some gifts for my son's birthday. I was picking up the Strategy Manual for the new Pokemon Black and White game for him when I noticed the manual for World of Warcraft: Cataclysm on the shelf nearby. I'm not a WoW player, but I can appreciate good artwork and fantasy-type creatures so I picked it up and started looking through it. When I got to the Tauren, I have to admit my heart sank. I’ve been aware of them, but their general resemblance to my Tylnor was suddenly much more disheartening than previously felt. (Oh, and the resemblance between the names Tylnor and Tauren is coincidental. The word Tylnor actually had a voiced stop at the beginning, but I liked the sound of the unvoiced one after all.) You be the judge on looks. Here are some images of Tauren; here is an early version of one of my Tylnor. The Tylnor originally (literally almost thirty years ago) began as my world's gnomes or dwarves and evolved since then into the horned critters you see here. The most recent version came about, originally, when I thought it would be cool to have them with horns, sort of built-in (stereotypical) vikings. Turns out there’s lots of fantasy creatures with horns, so that’s not that original after all. Okay, I thought, no problem. I thought some more and thought maybe I’ll pattern them after my favorite animal: the muskox. So, recently, I’ve added a large, hair-covered boss on their heads from which their horns sweep down on either side. Tylnor arms, legs, and backs also have long, shaggy guard-hairs. I haven’t decided if they’d need to be combed annually. That might set up some interesting cultural features. In any case, the Tylnor are humanoids patterned off a bovine or caprine form (muskoxen are actually related to goats), and that picture of the Tauren just made me think %$#@&! Do I have to entirely revamp the Tylnor? I’ve even gone so far as to investigate Tylnor skeletal structure, and I think I’ve determined they have a characteristic natural hump on their back from something that might be considered kyphosis in humans along with some spines on their thoracic vertebrae to hold up their massive heads and horns. Anyway, that’s all in the planning stages. Plus, of course, the Tauren themselves aren’t even original: Minotaur anyone?

Additionally, a year or so ago, I posted an image of my Drushek on ZBB and someone astutely noted "That looks like a Bothan." And, sure enough, if it didn’t, which led me at the time to say %$#@&! So, I’ve also gone back and redesigned those guys a bit, too. They now have a different hair-style, ears, and long thing tendrils on the corners of their mouths and chin. I haven’t decided whether their hair is more cilia-like or actual hair. They’re still hopping creatures though. I’m keeping that.

And then we come to language. This is a conlanging blog after all. The shorthand for this urge to be unique/original but you’re not, is ANADEW as used on CONLANG-L. For those who don’t know, ANADEW stands for “A natlang’s already dunnit, except worse” (See here.) Even my own Dritok has parallels in reality (whistled languages, sign languages, etc.). My only claim to fame may be that I insisted on including the nasal-ingressive voiceless velar trill as a regular phoneme. Even those who try to create an a priori conlang are often constrained by what their own mouths can produce. Notable exceptions to this are Rikchik and Fith. I’m in the process of formalizing Dritok and Umod (the Tylnor’s language) and eventually Elasin (another race’s language living in the same conworld), but it gets disheartening sometimes. I’m toying with the idea of using a bilabial trill in Umod. This is a stereotypical sound a horse or cow makes, so I felt it would fit the physiology. But, on the other hand, I don’t want to go too overboard on the exotic phonetics. But, on the other hand… Well, you get the idea.

In some ways, I’m hoping my having concerns like this makes me a better conlanger. At least, I’m thinking.

Thanks for listening. Whine-fest over. Back to the notebooks and drawing pad!

One Conlanger to Rule Them All

Today, I downloaded the relatively-recent English translation of Kirill Eskov‘s ПоÑледний кольценоÑец (The Last Ringbearer), the story of JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings as told from the viewpoint of Mordor and its inhabitants.

I’m only a couple chapters into it, but it got me thinking: Conlangers should really root for Sauron in Tolkien’s work, because Sauron is a conlanger! From what we know, he singlehandedly devised the Black Speech to be used by those who serve him.

Well, that wasn’t very satisfying. After all, Sauron is the bad guy. (At least in Tolkien’s work, not Eskov’s). Who wants to root for the bad guy? (Although, I must admit, I thought Darth Vader was the coolest until I found out he was Luke’s father. Ew! And, mind you, this was way back when A New Hope was the first Star Wars film. But I digress…) So, I started thinking, and remembered Aulë who created the Dwarves and devised a language for them, Khuzdul. It’s interesting to keep in mind that Sauron was originally one of the Maiar of Aulë.

To the best of my knowledge, Aulë and Sauron are the only two conlangers in Middle-earth. Yes, it’s true a couple elves (i.e., Rúmil and Fëanor) devised writing systems, but they didn’t create entire languages.

So, who ya gonna root for? Ash durbatulûk.“

The Stone Dance of Ice and Fire: A Double Review

I’ve recently been reading two fantasy series that, on reflection, have both parallels as well as sharp contrasts. The two series are:

- A Song of Ice and Fire by George R.R. Martin

- The Stone Dance of the Chameleon by Ricardo Pinto

I’ve read all four extant volumes of Martin's (unfinished) series (beginning with A Game of Thrones) and the first volume of Pinto's work (The Chosen) and just picked up the second.

What I found interesting right away is that both are concerned with what Martin calls "the game of thrones," the intrigue and political maneuvering (not to mention bloodshed) that goes with the choosing of who will have power in a certain time and place. I like both series, so let's take a look at them.

A Song of Ice and Fire is definitely a ripping yarn full of fully-rounded characters, lavish set pieces, and enough detail to provide a reader with page-turning enjoyment. Martin's strength is, without a doubt, his ability to engage the reader emotionally, to make him or her care about the fictional characters. This is one of the reasons, in my opinion, that fans are so passionate about Martin "finishing" the series. They care what happens to Arya, Brandon, Jaime, Cersei, and the rest of them. Did Sandor Clegane survive? Does Daenerys get to ride her dragons? What becomes of Brienne the Beautiful? I’d like to know, too.

On the other hand, as a world-builder, Martin is a little less successful. One person I know described Westeros as the perfect stereotype of what a fantasy world should be. Granted, the idea of winter lasting years is an intriguing fantastical feature, but the idea of why this happens is always nagging at me. No satisfactory (or any) explanation is ever given. It just is. Also, Martin insists on providing measurements for at least two edifices that would be better served by just saying they’re really, really big. First, The Wall is always 700 feet tall. Second, one of the pyramids that Daenerys rules over is 800 feet tall. For comparison, the Arc de Triomphe is 164 feet tall, the Great Pyramid of Giza is 481 feet tall, and Hoover Dam is 726.4 feet tall. Just imagine the sheer volume of structure like the Wall that is 700 feet tall and miles and miles long. From the description in the book, it would appear that The Wall has been extremely tall for ages and ages, and the pyramid Daenerys sits on is even taller than the Hoover Dam? I like my fantasy’s fantastical, but sometimes less detail is more.

Another nitpicky pet peeve (Yes, I realize I'm being nitpicky) is Martin's insistence on detailing many of the meals people eat. For example, "They broke their fast on black bread and boiled goose eggs and fish fried with onions and bacon…" Lampreys seem to be popular fare in Westeros as well. Dany nibbles "tree eggs, locust pie, and green noodles…" In some ways, it appears Martin wants to avoid the clichéd non-descript stew of some fantasy worlds, but, from my perspective, veers a little too far in the opposite direction.

Finally, since this is a conlanging blog, we come to language. Martin himself freely admits that "I suck at foreign languages. Always have. Always will." (Of course, now we can thank David Peterson for breathing life into Dothraki.) So, we really can't fault Martin for not creating an entire Dothraki or Valyrian language and including it in Appendices. He acknowledges that particular shortcoming. However, my beef with him is his sometimes completely random-seeming choice of names for characters and places, even within the same family: Cersei and Jaime; Robert, Stannis, and Renly, etc. Martin also has an annoying habit of combining a first-rate fantasy name with an English-sounding one: Davos Seaworth, Balon Greyjoy, Robert Baratheon, etc. The "almost" names and titles are somewhat annoying as well: Eddard = Edward, Joffrey = Jeffrey, Ser = Sir, Maester = Master, Denys = Dennis, Walder = Walter, Yohn = John, etc. He has somewhat better imagination with the Targaryens and when he gets out of Westeros (although his non-Westerosi names can appear a little unpronounceable): Xaro Xhoan Daxos (I ended up pronouncing x as [S] and xh as [Z] in my head), Jaqen H’ghar, the Dothraki names and words, Illyrio Mopatis, Mirri Maz Duur, etc. Those names sound and look consistently exotic and fantasical.

In the end, I don't have HBO making a TV series of anything I've ever written, and Martin's books have sold millions of copies; so who am I to pass judgement on the above shortcomings. I will say that for all their high-quality entertainment value, A Song of Ice and Fire does exhibit a lot of the tropes of fantasy literature (See the TV Tropes entry for the series here). I'm just sayin'.

Martin's series is interesting to see in juxtaposition with Pinto's The Stone Dance of the Chameleon. Where Martin's Seven Kingdoms and beyond are in many ways very familiar with their kings, knights, lords, and ladies, Pinto paints a thoroughly-detailed completely new creation for us: The Three Lands. This is not a thinly-veiled medieval European setting, but a world full of unfamiliar places and cultures where the simple act of forgetting to don one's mask can result in the deaths of scores of people. While Pinto cannot match Martin for sheer page-turning lively action, he does outmatch him for sheer ingenuity and attention to detail in world-building. Where Martin's sers ride horses, Pinto's Chosen mount saurian aquars and ride along horned huimurs. Where cloth-of-gold is popular in Westeros, it's usually cut into a tunic, doublet, or elaborate gown. In the paradisal seclusion of Pinto's Osrakum, the Chosen dress in elaborate court-robes, stilt-like shoes, and utilize slaves whose eyes have been replaced by precious stones. Pinto's website testifies to his detailed world-building when you see images from his notes with captions like "Detail from Notebook 18, Page 22". He even gives credit to someone in the acknowledgments for helping him with "the equations to calculate the lengths and directions of shadows." Whew!

Of course, all this planning and detail sometimes get in the way of telling a good story. Carnelian, the viewpoint character of the novels, is often staring, marveling, being overwhelmed, and having other superlative experiences while we're provided with a litany of detailed descriptions of the wonders Pinto has devised for us. It (usually) stops just short of being tiresome, and then the story resumes.

In one way, Martin and Pinto do have something in common in some of their naming practices: the "almost" names. For Pinto, they're based on gemstones or other precious materials: Osidian = obsidian, Jaspar = jasper, Aurum = gold (Latin), Opalid = opal, Molochite = malachite, etc. I believe I read that Pinto had at first almost used names in Quya but later decided against it.

Quya? What is this Quya? Here is where Pinto and Martin firmly part company. Pinto has an entire language and writing system for his world although, sadly, this does not show up very much in the books themselves. For those interested, he has extensive notes and a grammar on his website. According to the Acknowledgments, he had help with the language from David Adger. The writing system obviously has a debt to pay to the Mayan glyphs but has a beauty all its own and provides chapter heading glyphs from the first two books. There is only one extended text example, so it's a shame we don't see more of the language in the books themselves given Pinto's love of dazzling the reader with details.

Both series have something to offer and are well worth reading. If you like fast-paced storytelling, well-rounded characters, and cliffhanger endings, you can’t go wrong with A Song of Ice and Fire. If you like a more leisurely reading experience, very interesting characters, first-class worldbuilding (with (online) Appendices), try The Stone Dance of the Chameleon. See you in Westeros and Osrakum!

Overdue Posting… A Great Day in San Diego!

Waay back in January, I was in San Diego for the American Library Association Midwinter Meeting (as part of my job, not as The Conlanging Librarian). Being rarely in California, I took the chance to contact David Peterson and ask if he wanted to get together on Sunday afternoon. Well, the “event” took on a life of its own and, before I knew it, Sylvia Sotomayor was coming along and John Quijada was flying in for the day from northern California. I hadn’t seen any of them since LCC2 back in 2007, so I was very excited to get to hang out with my conlanging brethren and sistren.

Waay back in January, I was in San Diego for the American Library Association Midwinter Meeting (as part of my job, not as The Conlanging Librarian). Being rarely in California, I took the chance to contact David Peterson and ask if he wanted to get together on Sunday afternoon. Well, the “event” took on a life of its own and, before I knew it, Sylvia Sotomayor was coming along and John Quijada was flying in for the day from northern California. I hadn’t seen any of them since LCC2 back in 2007, so I was very excited to get to hang out with my conlanging brethren and sistren.

Having some official work-related duties on Sunday morning, I met up with them near the marina behind the convention center for lunch. Using the wonders of modern technology, we triangulated and coordinated and finally met for hugs and handshakes all around. We all piled into David’s natural-gas-powered automobile and headed over to Old Town for lunch. The pozole was great!

After lunch we traveled to the Gaslamp District in San Diego proper and walked around, had some snacks, and just got a chance to talk. The photo to the right is of Sylvia, David, and John sitting in Horton Plaza, an M.C. Escher of a venue if I ever saw one. Very cool.

As David’s already tweeted, this was a fantastic day. Not only did I get to hang out with some quintessential conlangers, two recipients of the Smiley Award (and its originator), and the creator of Dothraki, but David, Sylvia, and John are some of the most personable, friendly, and interesting people I’ve had the opportunity to meet. Thanks for a great day (and sorry it’s taken me so long to say so!)

Fun with the Ngram Viewer

I just found the new Ngram Viewer from Google Labs. This new tool allows for searches of specific words in Google Books and displays them as a graph. Playing around with some conlang-related terms, I found:

- Poor conlang doesn’t even register.

- Esperanto shows a peak around the 1930s.

- Klingon peaks in 2001.

- Volapuk (yes, sans umlaut) had it’s highest occurrence between 1880 and 2008 in 1898, with a steady decline since then.

One has to remember that two words typed in the search box without quotes can occur across sentence boundaries as well as in contexts other than the one intended. I tried the phrase constructed language and while it does have a number of occurrences pertaining to our favorite craft, it also has occurrences like “Certainly every science should seek for a well constructed language ; but it were to take the effect for the cause, to suppose that there are well established sciences, because there are well formed languages” (Elements of Psychology, 1834).

In any case, it’s an interesting tool and just plain fun to play around with.

Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes: A Conlanger’s Review

Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle recounts the experiences and research of author Daniel Everett with the Pirahã. Their language, also known as Pirahã, is notorious in linguistics circles for numerous traits uncovered by Everett. The New Yorker published an extensive article about Everett and his work in 2007 that does a good job of introducing readers to the controversy. Being neither a professional linguist nor having a particular linguistic axe to grind, I can’t contribute anything to that debate (nor would I want to wade into those waters); however, I can share some thoughts on the book and its story from a layperson’s perspective as well as provide some interesting conlinguistic titbits that the book has to offer.

The book’s title comes from a common "Good night" phrase that the Pirahã say and is good advice for a culture living deep in the Amazon jungle. The native culture in which Everett and his family find themselves is vividly portrayed (and not sugar-coated). The book’s first section, roughly two-thirds, recounts the story of Everett and his family among the Pirahã; the last third goes into more depth on the Pirahã language itself. Both sections are fascinating and include glimpses of the missionary zeal of Everett and his wife, unsettling cultural practices of the Pirahã, humorous cross-cultural incidents, and much more.

As usual, in book reviews here at The Conlanging Librarian, let’s examine some interesting linguistic twists that an enterprising conlanger might take advantage of from Pirahã. We’ll avoid the ones that many people may already know, including the language’s lack of recursion (see here). The first concept that struck me was the idea of kagi. Let’s take some examples from the text to see this in action first:

- “rice and beans” could be termed "rice with kagi"

- Dan arrives in the village with his children: "Dan arrived with kagi"

- Dan arrives in the vilage with his wife: "Dan arrived with kagi"

- A person goes to hunt with his dogs: "He went hunting with kagi"

Everett ends up translating the term kagi as "expected associate" with the expectation being culturally determined. A man's wife is expected to be associated with him. One expects a person to go hunting with his dogs. And so on.

The terms bigí and xoí are also associated with a culturally-determined meaning. The Pirahã believe in a layered universe. The bigí is the boundary between those layers. The xoí is the entire biosphere between bigí. To go into the jungle is to go deeper into the xoí. To remain motionless in a boat is to stay still in the xoí. If something falls from the sky, it may be said to come from the upper bigí. This way of dividing up the universe is similar in some ways to the way Deutscher described splitting up the visible spectrum in his book. Deutscher’s book also mentions fixed directional systems, and the Pirahã also use an upriver-downriver fixed point system instead of our left-right orientation. I still find this an interesting set of concepts to play with in a conlang.

Everett also contends that the Pirahã do not have a number system. According to him, they use a system of relative volume: hoi can appear to mean "two" but, in reality, can mean simply that two small fish or one medium fish are relatively smaller that a hoi fish. Everett recounts the trials of attempting to teach a number of Pirahãs to count in Portuguese, with very little success. He even goes so far as to say that there are not even words for quanitifers like "all, each, every, and so on." Instead, there are "quantifierlike" words (or affixes) that translate as "the bulk of" (Lit., the bigness of) the people went swimming and other relative terms. There are other words that mean the whole or part of something (usually something eaten). This way of looking at amounts, numbers, portions, etc., is fertile ground on which to play once again.

Finally (but no means the last intriguing concept in the book), Everett talks about the tribe's use of the term xibipíío which, loosely translated, means something like "the act of just entering or leaving perception, that is, a being on the boundaries of experience". "The match began to flicker. The men commented, 'The match is xibipíío-ing' . . . A flickering flame is a flame that repeatedly comes and goes out of experience or perception." However, the word can also be used for someone disappearing in a canoe around the bend in a river or for an airplane that just comes into view over the trees. The word has much wider connotations that an English-speaker saying something appears or disappears.

I have no idea what Everett thinks of conlangers or the art of language creation or if he is even aware of us. The final section of the book is entitled "Why Care About Other Cultures and Languages?" and lays out a good rationale for why this is important. In the end, there really is no comparison between language creation and preserving endangered languages. As M.S. Soderquist said on CONLANG-L: Creating a new hobby language doesn’t affect natural languages any more than playing Monopoly affects the economy. Conlangers can get their inspirations from any source, and Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle is a treasure trove of novel ideas as well as a a glimpse into another world and another culture and another way of seeing the world.

Catford’s Phonetics: An Essential Resource!

Although J.C. Catford’s A Practical Introduction to Phonetics has been part of The Conlanger’s Library for some time, it was only recently that I sought it out in the library to take a look. I have a recent (Nov. 4, 2010) posting of a glowing recommendation of the book on the CONLANG listserv for bringing it back to my attention. Luckily, my day job is at a large public library, and it was on the shelf just waiting for me to pick up.

The brief biography on the cover of the book states simply that J.C. Catford is “widely regarded as the leading practical phonetician of our time.” According to his obituary posted online, he was also “famous for his amazing ability to repeat speech backwards” and recorded Jabberwocky in this way (backwards and forwards) for the BBC. In his retirement, Prof. Catford worked on Ubykh, “a language of 80 consonants and just two vowels!” So, maybe it’s no wonder that Amazon.com lists as one of the “Customers Who Bought This Item [i.e., A Practical Introduction to Phonetics] Also Bought” Mark Rosenfelder’s Language Construction Kit.

His work itself is absolutely essential for conlangers who wish to include “exotic” (i.e., non-English) phonetics in their works. Catford takes the reader step-by-step through initiation, articulation, phonation, co-articulation, and much, much more. What is so valuable about the book is Catford’s Exercises (over 120 in all) throughout where he clearly shows how to pronounce every sound he discusses. I personally knew I may have to end up owning a copy of this when I found the following exercise clearly explaining how my own Drushek pronounce their “ejectives” (which I now know are actually pronounced by a velaric initiatory mechanism):

Say a velaric suction [|\ [in X-SAMPA, a dental click]]. Now immediately after the sucking movement of the tongue and the release of the tongue-tip contact, remake the contact and reverse the tongue-movement — that is, press instead of sucking — then release the tongue-tip contact again. The result should be a velaric pressure sound, for which there is no special symbol, so we shall represent it by [|\^ [again, in X-SAMPA]]. Continue to alternate velaric suction [|\] and velaric [|\^]: [|\], [|\^], [|\], [|\^] . . .

All this must be done without ever releasing the essential velaric (k-type) initiatory closure. We will now demonstrate that velaric initiation, whether of suction or pressure type, utilizes only the small amount of air trapped between the tongue-centre and an articulatory closure further forward in the mouth. To carry out this demonstration make a prolonged series of velaric sounds, for example [|\], [|\], [|\], and while continuing to do this, breathe in and out rather noisily through your nose. The experiment should be repeated with hum substituted for breath. Make a series of [|\] sounds while uninterruptedly humming through the nose. This proves that the velaric initiatory mechanism is completely independent of the pulmonic air-stream — it uses only the air trapped in the mouth in front of the velaric closure.

And this is just one of the exercises. I’m considering a voiced bilabial trill for one of my other languages and had never even considered a bidental fricative before now. Granted, one has to be careful to not make a kitchen-sink phonology, but a careful choice among the myriad sounds offered by Catford’s book can go a long way to giving one’s conlang any Sprachgefühl one wishes.

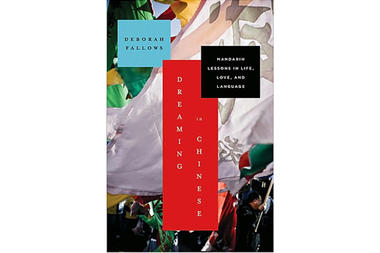

Dreaming In Chinese: A Review

Dreaming in Chinese: Mandarin Lessons in Life, Love, and Language by Deborah Fallows is a highly enjoyable read for those interested in learning about the language spoken by over 1.2 billion people (depending on how you define "Chinese"). There are a number of favorable reviews of Fallows' book online (including here, here, and here). Personally, I disagree with the CS Monitor's review in wanting "a more cohesive narrative arc". I don’t think that was the point. I saw this as “a Sunday newspaper column” collection and enjoyed them for the taste of Chinese culture and language that they provided; a table full of dim sum, if you will.

So, what does Dreaming in Chinese have to offer the average conlanger? Many will no doubt already be familiar with Chinese, but Fallows provides a good cultural-context overview for artlangers to consider. One example is the "overuse" by Americans of "Please", "Thank you", and other politeness words and phrases being seen as superfluous in that it puts distance between two speakers. This is in the "When rude is polite" chapter introduced by the phrase Bú yào " Don't want, don't need". Sounds like Klingon, but for entirely different "cultural" reasons.

One thing that everyone seems to know about Chinese is its use of tones and its limited syllables. Fallows does a great job of highlighting this in her chapter entitled "Language play as a national sport" (introduced by the words Shī, shí, shî, shì "Lion, ten, to make, to be"). The author brings up Chao Yuen Ren who wrote a story entitled "The Lion-eating Poet in the Stone Den" composed of 92 characters, all of various tones of the syllable shi. Tones are used by a little over 41% of the languages in the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS), whereas over at the Conlang Atlas (CALS), only a little over 24% use tones. This would appear to be a largely untapped feature for conlangs, although 30 conlangs at CALS do exhibit a (self-reported) "complex" tone system.

One conlang-specific item I was unaware of in relation to China was the extent to which Esperanto has been studied there. In her chapter entitled "A billion people; countless dialects", Fallows talks about Esperanto once being suggested as a common national language although it "was quickly abandoned as a far-out idea". The author's first family visit to China was as part of the World Esperanto Congress in Beijing in 1986.

Overall, Fallows does an excellent job of fulfilling her stated purpose with the book: to tell "the story of what I learned about the Chinese language, and what the language taught me about China." One is not going to learn all the idiosyncracies or fine grammatical points about Chinese, but if you’re looking for a user-friendly introduction to the fascinating language and culture of the Middle Kingdom, Dreaming in Chinese is highly recommended.